- Carbon monoxide (CO) is hazardous primarily because of its toxicity.

- Most industrial exposure occurs from the incomplete combustion of fuel to generate power, energy, or heat for various industrial processes.

- Workers in chemical manufacturing, metallurgy, semiconductor manufacturing, and healthcare may be exposed to CO, as the gas is used in these industries.

- Practically no industry is safe from the risk of CO poisoning, and all should use detectors to monitor the gas.

Carbon monoxide is among the most hazardous gases, and exposure can cause severe health problems. It is found in many places in factories, residences, and public spaces, and is called the “silent killer.” Carbon monoxide is one of the top four hazardous gases affecting workers’ health. It leads to the most injuries and evacuations and the second-highest number of fatalities due to chemicals in industries, according to the CDC. Nearly half of fatalities can be prevented with carbon monoxide detectors, and most are preventable when machines that emit the gas are correctly installed, operated, and maintained. However, the number of people affected by carbon monoxide poisoning has not improved, so this article discusses industries that can benefit from carbon monoxide monitoring.

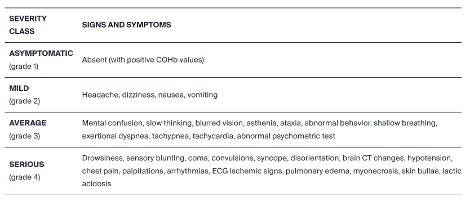

Table 1: “Classification of CO intoxication according to the Italian SIMEU guidelines,” Savioli et al. (2024). (Credits. https://www.mdpi.com/2077-0383/13/9/2466)

Why Carbon Monoxide Should be Monitored

Carbon monoxide (CO) is dangerous and should be monitored because it is colorless, odorless, tasteless, and non-irritating, making it undetectable to people. People can be exposed to CO without realizing it. Prolonged exposure even to low concentrations can be poisonous.

Carbon monoxide enters the body through inhalation. Hemoglobin, the red blood cells, combine with CO, to which they have an affinity 300 times stronger than to oxygen. So even exposure to low concentrations of CO significantly reduces the blood’s oxygen-carrying capacity, leading to weakness, headache, nausea, rapid breathing, exhaustion, and dizziness. Hypoxia or oxygen-deficiency, due to acute CO exposure, is a critical condition, which can cause long-term and irreversible neurological or cardiological effects. Exposure to high concentrations causes damage to the heart, brain, and respiratory system, and ultimately leads to death in a very short time. See Table 1 for a list of ailments caused by CO. Most CO poisoning and deaths are preventable with adequate precautions.

CO is naturally produced by volcanoes, forest fires, and lightning. Insufficient oxygen to burn any fuel produces CO instead of carbon dioxide. Artificially, CO is created by incomplete combustion in machines that use fuel, such as vehicles, power plants, and heating systems. Therefore, CO danger is ubiquitous and exists in homes and buildings with fuel-heating systems.

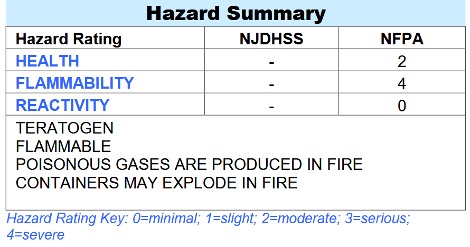

Table 2: Properties of Carbon Monoxide that make it an occupational hazard, NJ.Gov. (Credits: https://nj.gov/health/eoh/rtkweb/documents/fs/0345.pdf)

Carbon Monoxide in Industries

In the US, nearly 12% of CO poisonings reported that the workplace was the site of exposure. CO was the leading cause of occupational fatalities in the 1990s in the US.

CO is a crucial raw material in many manufacturing processes and is widely used across industries. Improper handling and accidental leaks can endanger workers. CO is highly reactive and flammable. In industrial settings, the accumulation of CO in poorly ventilated areas and confined spaces increases the risk of poisoning, fires, and explosions (see Table 2).

Given the dangers CO poses, strict exposure limits have been set for its presence in industries in the USA:

- The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) sets permissible exposure limits (PEL) for an 8-hour workshift average to 50 ppm. The PEL is legally binding.

- The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) has set an average recommended exposure limit (REL) for a 10-hour workshift of 35 ppm. CO concentrations may not exceed 200 ppm in any 15-minute period.

- The American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists (ACGIH) threshold limit value (TLV) is 25 ppm, averaged over an 8-hour workshift.

Precise gas analyzers used in industry can monitor air and detect minute changes of 1 ppm, even in small leaks. When gas levels exceed the PEL, audio and video alarms alert staff to prompt an evacuation, while management can take corrective actions before people and the facility are harmed. Many devices, such as Interscan’s CO fixed gas analyzers, include several sensors connected to a central unit that continuously monitor the air around the clock and offer datalogging capabilities to track trends in emissions. Moreover, the gas detectors can be integrated with sophisticated management software for quick control. Such monitoring devices allow industry owners to implement safety standards to comply with national regulations.

Two groups of industries must monitor CO: those that produce it as a byproduct of incomplete combustion and those that use it as a raw material in their industrial processes.

Producers of CO: All Industries Should Monitor Carbon Monoxide

Industries that burn fossil fuels, charcoal, plastics, and wood should also monitor CO levels to ensure they remain within safe levels. These industries burn fuel in generators, boilers, industrial furnaces, blast furnaces, coal ovens, vehicles (cars, trucks, and forklifts), machines, gas appliances (space heaters, water heaters, furnaces, and stoves), and kilns (coke and lime). Offices with combustion-heating systems should also monitor the air in occupied rooms and areas near machines that can emit CO. This list covers most establishments.

According to OSHA, the people working in close contact with CO emitters, especially in enclosed areas, performing the following tasks are most at risk from CO poisoning:

- Forklift operator

- Garage mechanic

- Firefighter

- Diesel engine operator

- Brewery operators

- Taxi driver

- Police Officer

- Welder

- Customs inspector

- Toll booth or tunnel attendant

- Carbon-black maker

- Metal oxide reducer

- Organic chemical synthesizer

- Marine terminal worker

- Longshore worker

- Kitchen worker

- Glass manufacturers

- Pulp and paper workers

Many of these workers are not industry-specific and can be involved across several sectors. However, workers in some industries are at greater risk of CO exposure because it is produced during their processes; these industries are discussed below.

-

Environmental Testing Industries

CO is a major air pollutant that threatens public health outside homes and factories. It is one of the gases monitored in the environment because of the significant harm it causes to human health. The danger to the public can come from industries, forest fires, agricultural waste burning, mines, and marshes. CO monitoring in the environment is necessary for various reasons, as listed below:

- Direct effects: In busy urban centers, people can be exposed to CO that accumulates from various sources. These can include underground garages, train passenger compartments, and high-traffic areas. People exposed to CO in these places daily can suffer from illness.

- Indirect effect: CO rises into the troposphere and reacts with nitrogen oxides (NOx) to form ozone. Ozone is a toxic gas that causes fatalities. For example, ozone causes the deaths of 50,000 Chinese annually, and CO is one of its precursors, along with VOCs and NOx.

-

Underground Mining

Underground coal and metal ore mines must monitor air for CO because limited ventilation reduces the gas buildup from machinery and vehicles. Often, the main source of CO in coal mines is diesel engines. Detonations also produce CO.

Fires in mines are another source of CO. In the event of a fire in mines, the CO produced does not stay near the fire. Along with other combustion products, CO spreads through the mine, poisoning miners. For example, a conveyor belt fire in Aracoma Alma Mine exposed two miners to CO, killing them, when they were separated from the rest of the crew during evacuation. CO-related dangers must be considered when designing ventilation systems, emergency response plans, and evacuation and rescue procedures for workers. Software packages use fire simulation to predict CO levels and pathways for fire emergencies, escape planning, and firefighting.

-

Power Generation Plants

Plants that generate energy and power from coal, gas, or biomass gasification produce high concentrations of pollutants. Therefore, these facilities should monitor CO to keep their staff safe and healthy.

-

Metallurgy

During steel manufacturing, the blast furnaces emit blast furnace gas, which contains 20-28 mol% of carbon monoxide. It is mixed with several other gases, such as carbon dioxide, nitrogen, hydrogen, methane, hydrogen sulfide, and other sulfur compounds. Given the importance of CO as a raw material, efforts are underway to separate it from other gases for use in steel plants. However, steel manufacturing facilities must safeguard their workers by installing detectors.

Other metallurgy and engineering facilities involving ovens, welding, blowtorch use, and engines should also monitor CO. Carbon monoxide is used as a reducing agent in metallurgy for nickel recovery in the Mond process.

-

Petroleum Refineries

The petroleum refineries are a major source of air pollution. The emissions include 22% CO, the third-largest component of the mixture. Combustion emissions account for the largest share of total emissions. CO emissions are produced by burning fossil fuels for refining. The equipment that produces emissions in refineries includes heaters, furnaces, and steam boilers used to generate heat for various processes. The fuels used can be liquid hydrocarbons, natural gas, and refinery gas.

Carbon monoxide is also used as a chemical agent in the Fischer-Tropsch process for producing petroleum-related products.

Besides protecting their workers, petroleum refineries, major sources of air pollution that pose health risks to surrounding communities, are also required to comply with environmental regulations and reduce CO emissions into the atmosphere.

-

Agriculture

Carbon monoxide is produced in agricultural practices when crop residue fires occur in the fields. Even though the fires are outdoors, the air pollution is substantial. For example, in India, farmers burn rice stubble after harvest to clear land for the next season. The method is still used due to its low cost. However, the fires release large amounts of particulate dust and toxic gases, including CO. These pollutants travel around 140 kms to reach New Delhi and contribute to 14% of the city’s pollution. The toxic air causes severe and widespread respiratory and cardiac health problems.

According to a study, agricultural residue burning in Punjab, north India, generates 194.83 ppbv of CO, significantly higher than normal levels of 40-50 ppbv recorded over remote oceans.

-

Industrial Fishing Industry

Fishing vessels should have CO detectors and have faulty equipment repaired to prevent CO emissions. Commercial and recreational scuba divers can be exposed to CO, which accumulates in hoses and equipment. For example, two fishermen were killed due to carbon monoxide poisoning while asleep in a closed room with a butane-fueled cooker used for heating, as the regular heaters were non-functional. The rooms had no gas sensors to alert the men to the CO danger.

To prevent such accidents at home, many countries have strict rules requiring CO alarms in rooms.

-

Firefighters

Firefighters are at a high risk of CO exposure. Firefighters can be exposed to CO during fire suppression, wildfire operations, overhaul, training, and confined spaces operations. Besides poisoning, firefighters can be injured in explosions by CO. Providing firefighters with individual wearable CO sensors can protect them and help assess dangers in the space they intend to enter.

Some other industries that need to monitor CO because of proven exposure to the gas in their facilities are those that manufacture siliceous products, such as cement, lime, plaster, and concrete.

Users of CO

Though CO is dangerous, it is also an important molecule used in the production of various materials and a crucial component in processes. Accidental leaks can occur during handling, storage, and transport in these industries, exposing staff to CO. Some of the most important industries that use CO are discussed below.

-

Healthcare

Carbon monoxide has potential medicinal properties, as it is cytoprotective and anti-inflammatory at low doses. It can have therapeutic effects for ischemic injuries and organ transplantation. However, there is a risk of exposing medical staff to high levels of CO due to insufficient ventilation, inappropriate equipment, and improper calibration when the correct dose is not administered. Considering these risks has so far hampered the use of CO in clinics. If CO use becomes a regular practice, using gas sensors to detect CO levels at the ppb (parts per billion) level can avert disasters.

-

Chemical Manufacturing

Carbon monoxide is considered one of the essential building blocks for many organic and fine chemical compounds. It is necessary for the synthesis of several chemicals, synthetic fuels, and plastics. It is used in the chemical industry to produce acetic anhydride, acetic acid, polycarbonates, polyketones, and zinc white pigments. It is also an essential intermediary in the production of ammonia, urea, methanol, isocyanates, phosgene, oxo-alcohols, metal carbonyls, light hydrocarbons, and other chemicals.

Facilities that use CO for chemical production should monitor the air to detect accidental leaks.

-

Semiconductor

Pure carbon monoxide is one of the many compounds used in the semiconductor factories. CO is used to control etching profiles by regulating the etch rate. All the processes in the semiconductor industry are sensitive and require an atmosphere free of any contamination. So, gas sensors are necessary to ensure that no residual CO lingers and negatively affects subsequent procedures.

Preventing CO Poisoning

Nearly all CO poisonings are preventable through proper air monitoring, maintenance, and equipment installation. Some other suggestions include

- Moving power generators or other fossil-fuel machines outdoors to prevent CO accumulation indoors.

- Choose electrical energy sources to replace fuel-based equipment.

- Providing workers going into confined and poorly ventilated spaces with individual portable CO detectors.

Interscan offers both fixed and portable CO detection devices. The Portable GASD 8000 and the fixed AccuSafe can detect trace amounts of the gas to keep your workers safe.

Schedule a meeting with us for more information and demos of our Carbon monoxide detectors.

Sources

Afdhol, M. K., Yuliusman, & Hasibuan, M. Y. (2023). Adsorption of Methane and Carbon Monoxide from Petroleum Refineries Using Activated Carbon from Oil Palm Shells. AIP Conference Proceedings, 2431(1), Article 050003. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0114182

Dahmann, D., Morfeld, P., Monz, C., Noll, B., & Gast, F. (2009). Exposure assessment for nitrogen oxides and carbon monoxide in German hard coal mining. International archives of occupational and environmental health, 82(10), 1267-1279.

Graber, J. M., Macdonald, S. C., Kass, D. E., Smith, A. E., & Anderson, H. A. (2007). Carbon monoxide: the case for environmental public health surveillance. Public Health Reports, 122(2), 138-144.

Henn, S. A., Bell, J. L., Sussell, A. L., & Konda, S. (2013). Occupational carbon monoxide fatalities in the US from unintentional non-fire related exposures, 1992-2008. American journal of industrial medicine, 56(11), 1280–1289. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajim.22226

Ma, X., Albertsma, J., Gabriels, D., Horst, R., Polat, S., Snoeks, C., … & van der Veen, M. A. (2023). Carbon monoxide separation: past, present and future. Chemical Society Reviews, 52(11), 3741-3777.

Maitlis, P., & Haynes, A. (2006). Syntheses based on carbon monoxide. Metal-catalysis in industrial organic processes, 114-162. Doi:

https://doi.org/10.1039/9781847555328-00114

Mansourmoghaddam, M., Rousta, I., Olafsson, H., Tkaczyk, P., Chmiel, S., Baranowski, P., & Krzyszczak, J. (2023). Monitoring of Carbon Monoxide (CO) changes in the atmosphere and urban environmental indices extracted from remote sensing images for 932 Iran cities from 2019 to 2021. International Journal of Digital Earth, 16(1), 1205–1223. https://doi.org/10.1080/17538947.2023.2196445

Modern Diplomacy. (2025, May22). The Silent Killer: Why Every Industrial Zone Needs A Carbon Monoxide Gas Detector. Retrieved from https://moderndiplomacy.eu/2025/05/22/the-silent-killer-why-every-industrial-zone-needs-a-carbon-monoxide-gas-detector/

Mounika V, P I K, Siluvai S, et al. (November 19, 2024) Carbon Monoxide in Healthcare Monitoring Balancing Potential and Challenges in Public Health Perspective: A Narrative Review. Cureus 16(11): e74052. doi:10.7759/cureus.74052

NJ Health. (2016, Dec). Hazardous Substance Fact Sheet- Carbon Monoxide. Retrieved from

https://nj.gov/health/eoh/rtkweb/documents/fs/0345.pdf

NSW. (n.d.). Carbon monoxide technical fact sheet. Retrieved from https://www.safework.nsw.gov.au/resource-library/hazardous-chemicals/carbon-monoxide-technical-fact-sheet

OSHA. (n.d.). OSHA Fact sheet- Carbon Monoxide Poisoning. Retrieved from https://www.osha.gov/sites/default/files/publications/carbonmonoxide-factsheet.pdf

Rohrmann, C. A., Schiefelbein, G. F., Molton, P. M., Li, C. T., Elliott, D. C., & Baker, E. G. (1977). Chemical production from waste carbon monoxide: its potential for energy conservation (No. BNWL-2137). Battelle Pacific Northwest Labs., Richland, WA (United States).

Savioli, G., Gri, N., Ceresa, I. F., Piccioni, A., Zanza, C., Longhitano, Y., Ricevuti, G., Daccò, M., Esposito, C., & Candura, S. M. (2024). Carbon Monoxide Poisoning: From Occupational Health to Emergency Medicine. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(9), 2466. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13092466

Singh, V., Buelens, L. C., Poelman, H., Saeys, M., Marin, G. B., & Galvita, V. V. (2022). Carbon monoxide production using a steel mill gas in a combined chemical looping process. Journal of Energy Chemistry, 68, 811-825.

Tavella, R. A., da Silva Júnior, F. M. R., Santos, M. A., Miraglia, S. G. E. K., & Pereira Filho, R. D. (2025). A Review of Air Pollution from Petroleum Refining and Petrochemical Industrial Complexes: Sources, Key Pollutants, Health Impacts, and Challenges. ChemEngineering, 9(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemengineering9010013

Vadrevu, K. P., Giglio, L., & Justice, C. (2013). Satellite based analysis of fire–carbon monoxide relationships from forest and agricultural residue burning (2003–2011). Atmospheric environment, 64, 179-191.

Wilbur S, Williams M, Williams R, et al. (2012). Toxicological Profile for Carbon Monoxide. Atlanta (GA): Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (US); PRODUCTION, IMPORT/EXPORT, USE, AND DISPOSAL. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK153697/

Zhou, L., Yuan, L., Bahrami, D., Thomas, R. A., & Rowland, J. H. (2018). Numerical and experimental investigation of carbon monoxide spread in underground mine fires. Journal of fire sciences, 36(5), 406-418. https://www.mdpi.com/1424-8220/18/10/3443