- Chemicals of all forms- gases, liquids, and solids – can be occupational hazards.

- Gases are more dangerous than solids and liquids due to their difficulty in detecting, density changes, gas transport modes, faster reaction rates, compressibility, and the presence of confined spaces.

- Gas analyzers are essential for monitoring air in industrial settings to keep concentrations low and warn of unsafe accumulation levels, protecting workers and facilities.

Exposure to airborne particulate matter, gases, and fumes is the number one cause of occupational deaths in the world, according to a 2021 World Health Organization/International Labor Organization (WHO/ILO) Joint Estimates. It makes exposure to chemicals, including gases, one of the highest occupational risks in industries. While solids and liquids can also be hazardous, gases are more dangerous. The article seeks to identify reasons behind the increased risk posed by gases.

Hazardous Chemicals

Occupational hazards in industries can include chemical, physical, biological, safety, ergonomic, and/or psychosocial hazards. Chemicals- gases, liquids, and solids- are hazardous because they can all enter the body to harm people. Gaseous chemicals enter the body through inhalation, absorption through skin and eyes, and ingestion. It is not just gases, but also solids and liquids as aerosols, and solids as dust that can be inhaled. Contaminated hands and cigarettes also result in some ingestion of chemicals.

Gaseous chemicals pose significant hazards because they can be toxic, flammable, explosive, and corrosive.

Toxicity

Hundreds of inorganic and organic gases are used in industries. Because gases are colorless and odorless, people working in seemingly clean air can be exposed to poisonous ones.

Gases can cause mild illness to severe disease through acute or chronic exposure, depending on the chemical, its concentration in the air, and the duration and frequency of exposure. In many cases, health effects last a lifetime, and acute exposure to high concentrations of some gases, like hydrogen sulfide, can be immediately fatal.

Toxic gases are classified into four groups based on toxic intensity and five groups based on mode of action.

Chronic exposure to small doses of some gases, like ethylene dioxide, benzene, formaldehyde, and radon, causes cancer.

Yet other gases are inert, but can cause asphyxiation when they accumulate in poorly ventilated spaces in high enough concentrations to displace oxygen and cause its deficiency. For example, carbon dioxide, volatile organic compounds, methane, etc.

Fire and Explosion risk

Several gases are flammable and can cause fires and explosions when present in concentrations between their lower explosive limit (LEL) and upper explosive limit (UEL). The exact LEL above which a gas poses a fire or explosion risk is generally 5% by volume of air, but the exact values differ among gases. Flammable gases have a flashpoint, or minimum temperature for ignition, below 37.8°C (100°F). So, these gases can catch fire at room temperature when exposed to an ignition source.

Several common industrial gases are flammable, like methane, propane, hydrogen, hydrogen sulfide, ethylene, ammonia, acetylene, and carbon monoxide.

Fires and explosions involving flammable gases occur due to tasks such as welding, cutting, and brazing, damaged electrical equipment, improper storage, and the accumulation of combustible materials from poor housekeeping.

Among all chemicals, gases are more dangerous than liquids and solids for several reasons, including their gas transport properties, modes of absorption, compressibility, and difficulty in detection. These reasons will be discussed below.

Difficult to Detect

Most gases are colorless, and many are odorless, making them hard for people to detect. Whereas liquids and solids can be seen, most gases are not visible or smellable. Workers can therefore be exposed to harmful gases without realizing the danger. The difficulty in detection also prevents staff from looking for sources and attempting to curtail the gases. Consequently, gas concentrations can continue to rise, reaching harmful levels. However, fumes from solvents that vaporize or fine particulate matter from grinding and cutting can also be present in the air without detection. So, this differentiation exists from chemicals that retain their fixed liquid and solid forms, in which case they are easier to contain and clean up spills.

Density Changes

Gases move through convection and diffusion.

- Diffusion is the random movement of gases from areas of higher concentration to areas of lower concentration and is a slow process. This occurs at the molecular level, where each molecule moves randomly.

- Convection is the bulk movement of gas in a particular direction driven by temperature or pressure differences. Many molecules move together as a group, and the process is fast.

External environmental factors that affect gas convection can influence the distribution of gases in an area. Some gases are heavier than air and tend to settle close to the ground, while gases lighter than air tend to rise. However, unlike liquids and solids, gases have no fixed form and their volume changes with container size, ambient temperature, and pressure.

Changes in gas temperature can thus change buoyancy. Heavier gases that are warmer than the air can rise higher than usual, while gases colder than ambient temperatures will be denser and sink. The ability of processes to change density and gas temperature must be considered when placing sensors to detect gases in industry.

Gas Transport

Gases, fumes, and particulate matter can all be inhaled by workers. However, gases travel faster and further to other parts of the body because of their size. Gravitational deposition of aerosols and particulate matter larger than 100 μm removes them from the air due to settling onto nearby surfaces. Gases, which usually are smaller than 100 μm, stay airborne, and their speed is determined by temperature, relative humidity, and air velocity.

Once inhaled into the lungs, gas movement occurs by diffusion and is influenced by the concentration gradient, the length of the pathway, and the surface area. Higher gradients and surface area increase the diffusion rate, but longer pathways reduce it.

However, fine particles, a major health concern with diameters of 2.5 μm or less, especially ultrafine particles, can also enter the bloodstream like gases, even though coarse particles over 10 μm do not.

Faster Reaction

The diffusion of gases in lungs or in air is also determined by Graham’s Law, according to which the lower the mass of a gas, the faster it disperses.

Gas molecules move faster than those in liquids and solids, leading to more collisions with other molecules and, consequently, faster reaction rates. Factors, such as temperature, that increase the speed of movement will raise the rate of chemical reactions. This increased reactivity can lead to more harm when gases are toxic, corrosive, and flammable. Combined with the volatile nature of gases, which increases access to organs, their faster reaction rates make them more dangerous.

Compressibility

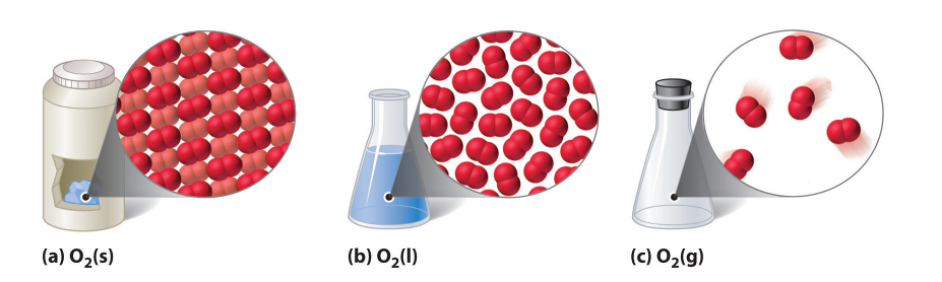

Another significant property of gas that distinguishes it from liquids and solids and makes it dangerous is its compressibility. Unlike solids and liquids, which have fixed volumes and cannot be compressed, gas volumes can be reduced by applying pressure, facilitating transport and storage, usually in cylinders (see Figure 1). Since more molecules are confined in a smaller container, gases exert greater pressure when compressed. In some cases, gas volumes are reduced by storing them as liquids. As a thumb rule, the volume of solids and liquids increases by 800 times when they form gases. For example, one gram of oxygen at its boiling point (-183oC) is a liquid and has a volume of 0.894 mL. At 0 °C and atmospheric pressure, its volume is 700 ml.

Figure 1: “A Representation of the Solid, Liquid, and Gas States. (a) Solid O2 has a fixed volume and shape, and the molecules are packed tightly together. (b) Liquid O2 conforms to the shape of its container but has a fixed volume; it contains relatively densely packed molecules. (c) Gaseous O2 fills its container completely—regardless of the container’s size or shape—and consists of widely separated molecules,” LibreTexts Chemistry

Pressurized gases are used in many industries for chemical processes, welding, metal cutting, fuel storage, medical uses, and water treatment. However, pressurized gases are an occupational risk due to the following reasons:

- Leaked or escaped gases can catch fire when they encounter an ignition source, if they are flammable.

- Escaped gas can cause explosions, especially when liquids suddenly expand.

- Liquified gases such as chlorine, nitrogen, or carbon dioxide can cool or freeze body parts during accidental release.

Faulty equipment, improper handling and storage, poor maintenance, insufficient ventilation, and inadequate training are the main causes of accidents involving pressurized gases. Fire and explosion can cause injuries, fatalities, and damage and destruction of industrial facilities.

Confined Spaces

The dangers posed by gases can be compounded in certain workplaces, such as confined spaces or areas with poor ventilation, where processes like welding, decomposition of plant and animal matter, chemical reactions, oxidation, and environmental conditions cause gases to accumulate.

- Due to the cramped and low ventilation, gases accumulate and can pose health risks if toxic.

- Oxygen depletion and increased carbon dioxide levels from workers’ breathing can cause asphyxiation.

- Flammable gases and combustible dust increase the risk of fire and explosion in confined spaces.

Gases are the number one cause of deaths in confined spaces of workers and would-be rescuers, besides physical hazards. Liquids and solids that are detectable pose a lower risk in these situations. Moreover, the greater number of gas molecules that can accumulate in a confined space increases their concentration per unit volume, unlike in liquids and solids.

Importance of Monitoring the Air

Because they are invisible, the only reliable way to detect gases is to monitor the air in industrial facilities for the hazardous gases industrial hygienists and safety managers expect to find. By strategically deploying fixed continuous gas analyzers at source points and high-risk areas, industries can monitor air quality to ensure hazardous gases remain below permissible limits and LELs. Many fixed systems have data-logging capabilities and can be used with management software to track gas-emission trends and control concentrations by shutting down relevant equipment. Portable gas detectors are suitable for checking gas concentrations in confined spaces before entry and during work. In both cases, the visual and audio alarms can alert workers to unsafe gas levels, allowing time for evacuation and for control measures to reduce risk to people and facilities.

Interscan offers fixed and portable gas detection systems with sensors for over 20 hazardous gases.

Contact us to learn more about our air quality monitoring products and request a quote.

Sources

American Lung Association. (n.d.). What Is Particle Pollution? Retrieved from https://www.lung.org/clean-air/outdoors/what-makes-air-unhealthy/particle-pollution#:~:text=Particulate%20matter%20air%20pollution%20is,heart%2C%20brain%20and%20other%20organs.

Bodner Research Web. (n.d.). The Properties of Gases. Retrieved from https://chemed.chem.purdue.edu/genchem/topicreview/bp/ch4/properties.php

Chemistry For Everyone. (2025). How Does Gas Diffusion Differ From Convection? – Chemistry For Everyone. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6KJ1l1vrv0Q&t=3s

LibreTexts Chemistry. (n.d.). Classifying Matter According to Its State—Solid, Liquid, and Gas. Retrieved from https://chem.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Introductory_Chemistry/Introductory_

Chemistry_(LibreTexts)/03%3A_Matter_and_Energy/3.03%3A_Classifying_Matter_According_to_Its_StateSolid_Liquid_and_Gas

Lim, J. W., & Koh, D. (2014). Chemical agents that cause occupational diseases. The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Health, Illness, Behavior, and Society.

Morawska, L., Buonanno, G., Mikszewski, A., & Stabile, L. (2022). The physics of respiratory particle generation, fate in the air, and inhalation. Nature reviews. Physics, 4(11), 723–734. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42254-022-00506-7

Stephan, L.R. (2021). Fast or Slow … Chemistry Makes It Go! Retrieved from https://www.acs.org/education/celebrating-chemistry-editions/2021-ncw/fast-or-slow.html

TeachMe Physiology. (n.d.). Gas exchange. Retrieved by https://teachmephysiology.com/respiratory-system/gas-exchange/gas-exchange/

WHO/ILO. (2021). WHO/ILO Joint Estimates of the Work-related Burden of Disease and Injury, 2000–2016. Retrieved from https://www.ilo.org/sites/default/files/wcmsp5/groups/public/@ed_dialogue/@lab_admin/documents/publication/wcms_819788.pdf